Magnum Contact Sheets

This is the best photography book of 2011 by a long-shot—not because the others were poor but because this one is just so good, so comprehensive, so big, so full of iconic photos and contact sheets. Part of the skill in being a real photographer comes from possessing the ability to effectively edit photos, and I’ve yet to see a better, more beautiful expression of the editing process than the one you’ll find here.

Moonwalking with Einstein by Joshua Foer

Last Sunday’s New York Times Magazine ran an excerpt of Joshua Foer’s new book about entering and winning the U.S. competitive memory championship. Foer, as you may have guessed, is the younger brother of Jonathan Safran and Franklin Foer. His book is excellent. There have been several documentaries and books over the past seven years or so about competitions that have ranged from somewhat obscure to downright bizarre. Fortunately, Foer’s book is about much more than the competition and his preparation for it. It uses bizarre feats of memory—the order of a deck of cards in under two minutes! 50,000 digits of pi!—as a starting point to explore the place that memory has in our culture—i.e. a decreasingly distinguished one. With the rise of the Internet and search engines, the ability to memorize things has become less and less important. Long before that, the invention of the written word had an even greater effect on rendering memory less necessary. You don’t actually have to know information; you need only know where to find it. Rote memorization is not as valuable as creativity, people tell us.

But yet there is a creativity in memorization and memory. Many of the techniques used in competitive memory involved coming up with outrageous—often disproportionate or obscene—visual images to help remember more banal items. The approach of competitive memory participants that most fascinated me, however, is that they imagine physical spaces in their minds and then populate them with memories. (The “memory palace” is a centuries-old technique for remembering.) Humans evolved to be hunter gatherers and, as Foer recounts, to have excellent spatial memories. Therefore, to remember things, memory gurus take their neighborhoods, homes, and offices, and fill them with memories. In Foer’s example of memorizing a shopping list, a giant jar of pickled garlic stands in front of his childhood home, a woman swims in cottage cheese on the front porch, and smoked salmon rests on the strings of a grand piano in the living room.

We don’t only remember spatial experiences, but we also find them valuable because they’re memorable. One of my issues with much of digital culture is that I find my experiences with it to be entirely unmemorable and, consequently, not valuable in retrospect. Sitting in front of my MacBook always involves the physical experience of sitting in front of my MacBook and typing away on the same keyboard, looking at the same screen. Whereas, reading the 800-page Gravity’s Rainbow is a markedly different physical experience from reading 180-page Great Gatsby, and both are significantly different from reading a photo book or a magazine. We remember discrete physical objects and our experiences with them, but when so much culture that we used to experience via disparate objects becomes concentrated in a small handful of digital devices, the memories that we associate with those experiences change. I’m not talking about being able to quote passages of a book or cite its main themes, but to remember the experience of reading it as distinct from the experience of reading another book or watching a film or browsing the web—to remember what it felt like.

Why People Photograph by Robert Adams

This is a slim little book of essays by photographer Robert Adams. I’ve often thought that the best writing about art comes not from professional critics and academics but from true fans or people who actually practice the art form about which they’re writing. Adams’s book only supports that opinion. My favorite line: “[Photographers] may not make a living by photography, but they are alive by it.”

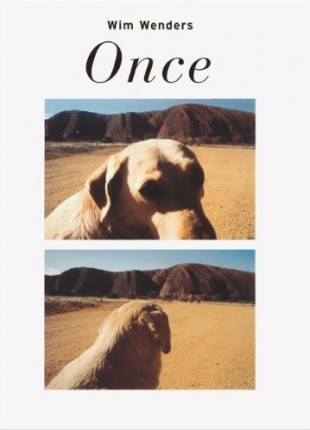

Once by Wim Wenders

I adore this book of photographs and text by Wim Wenders, much of which he shot while doing research for his films, which include Wings of Desire, Paris, Texas, and Buena Vista Social Club. Its title comes from the idea that photos don’t create ongoing moments, to steal the title of Geoff Dyer’s book; more than anything, they tell you that this happened once and will never happen again. Wenders concludes his volume:

“Once is not enough,”

I used to say as a kid.

That seemed very plausible to me,

“once upon a time.”

But when you take pictures,

I learned,

none of that applies.

Then once is

“once and for all.”

Comptoir de l’image

This store in the middle of the Marais in Paris could be notable for its collection of Vogue back issues alone. But it also happens to have an excellent selection of old photography books and is not to be missed if you’re in Paris and care at all about visual culture, fashion, photography, or seeing.

Comptoir de l’image 44 rue Sévigné, 75003 Paris